Forcing a file’s CRC to any value

Forcing a file’s CRC to any value

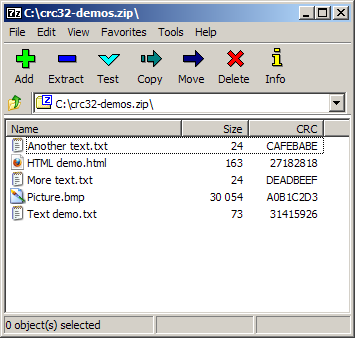

Example files: crc32-demos.zip

By modifying any 4 consecutive bytes in a file, you can change the file’s CRC to any value you choose. This technique is useful for vanity purposes, and also proves that the CRC-32 hash is extremely malleable and unsuitable for protecting a file from intentional modifications.

This page provides programs to demonstrate this technique and includes an explanation of the mathematics involved. Note that the technique is entirely algebraic – without guessing or using brute force, the program calculates the necessary modification to the file in one shot.

Source code

- Java: forcecrc32.java

-

Compile:

javac forcecrc32.java

Run:java forcecrc32 FileName ByteOffset NewCrc32Value

Example:java forcecrc32 picture.bmp 31337 DEADBEEF - Python: forcecrc32.py

-

Usage:

python forcecrc32.py FileName ByteOffset NewCrc32Value

Example:python forcecrc32.py document.txt 94 CAFEF00D - Rust: forcecrc32.rs

-

Compile:

rustc -O forcecrc32.rs

Run:./forcecrc32 FileName ByteOffset NewCrc32Value

Example:./forcecrc32 video.mp4 16777216 FEEDC0DE - C: forcecrc32.c

-

Compile:

cc forcecrc32.c -o forcecrc32

Run:./forcecrc32 FileName ByteOffset NewCrc32Value

Example:./forcecrc32 sound.wav 2807 88111188 - C++: forcecrc32.cpp

-

Compile:

c++ forcecrc32.cpp -o forcecrc32

Run:./forcecrc32 FileName ByteOffset NewCrc32Value

Example:./forcecrc32 bundle.zip 51234 FACEB00C

Notes:

All four language versions of the program have the same command-line arguments and behave the same. Simply choose the one that is most convenient in your computing environment.

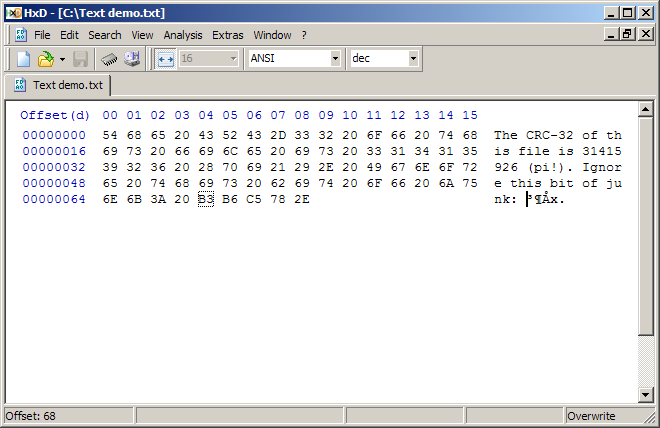

To find the appropriate byte offset in the file to make the modification, it is recommended to use a hex editor (e.g. HxD on Windows, GHex on Linux).

The program updates your specified file in place, but only changes the 4 bytes starting at ByteOffset. If you are unsure of what you’re doing, make a backup of the target file before running the program.

If you want to change the file’s CRC by appending 4 bytes, then simply append to the file 4 bytes of any value (e.g. 00) and point the program to patch those 4 bytes.

This software is open source, licensed under the GNU General Public License v3.0+.

Review of CRC-32

These are the steps to calculate the CRC-32 hash of any file or message:

Append the bytes 00 00 00 00 to the message.

XOR the initial 4 bytes by FF FF FF FF.

Interpret the sequence of bytes as a (very long) list of polynomial coefficients. Earlier bytes are assigned higher powers. Less significant bits are assigned higher powers. So for example, the hexadecimal byte sequence 01 C0 represents the sequence of polynomial coefficients 10000000 00000011, which represents the polynomial \(x^{15} + x^1 + x^0\).

Divide this preprocessed message polynomial by the CRC-32 generator polynomial[0] in \(\text{GF}(2)\) and keep only the remainder.

Interpret the remainder as a 32-bit integer by mapping less significant bits to higher powers. For example, the polynomial \(x^{31} + x^3 + x^1 + x^0\) is represented by the integer 0xD0000001.

XOR the value by 0xFFFFFFFF to obtain the CRC.

Forcing the CRC

The core of the CRC algorithm (including CRC-32 in particular) is polynomial division, where the polynomials have coefficients drawn from the finite field \(\text{GF}(2)\).

But to do more advanced analysis on the properties of CRCs, we need to adopt a more formal view of things. The underlying field for the coefficients is always \(\text{GF}(2)\). The generator polynomial defines a quotient ring[1], and now every polynomial we work with is an element of this ring. So the goal is to take the preprocessed message polynomial \(M(x)\) (which may have a degree greater than the generator polynomial’s degree) and reduce it to its canonical form by doing polynomial division. Remember that from now on, we treat each polynomial as a single object, and the result of each arithmetic operation is a polynomial object.

To force the CRC to any value we desire, read the following observations and derivation:

Let \(G(x)\) be the CRC generator polynomial.

Let \(n\) be the bit length of the original message. Let \(k\) be the chosen bit offset from the start of the message where the message will be modified.

Let \(M(x)\) be the preprocessed message polynomial.

Let \(R(x) ≡ M(x) \text{ mod } G(x)\) be the remainder polynomial, having degree less than \(G\)’s degree.

Let \(R'(x)\) be the new remainder chosen by the user.

Let \(D(x) ≡ R'(x) - R(x) \text{ mod } G(x)\). This is the delta for the remainder.

The act of modifying degree-of-\(G\) bits of the message \(M(x)\) at bit offset \(k\) means XORing those bits by some polynomial \(E(x)\).

Let \(M'(x)\) be the preprocessed message after modification, which we will compute.

Let \(E(x)\) be the delta applied to the message bits that will be modified, which we will compute.

Algebraically, we have that \(M'(x) ≡ M(x) + E(x) \, x^{n - k} \text{ mod } G(x)\).

We want \(M'(x) ≡ R'(x) \text{ mod } G(x)\). But we know \(M(x) ≡ R(x) \text{ mod } G(x)\).

Substitute and subtract to get \(E(x) ≡ D(x) \, (x^{n-k})^{-1} \mod G(x)\).

To summarize, in order to compute how to modify the message bytes, we need to calculate the difference between the current CRC and the desired CRC, calculate a polynomial power mod \(G(x)\), calculate a reciprocal mod \(G(x)\), and calculate a product mod \(G(x)\).

Notes

I was inspired to research and develop this technique when I saw fansubbed anime files that had peculiar CRCs, such as 13131313 for Doremi Fansub’s Mai-Otome episode 13 (released in January 2006). This is because it was conventional to include the file’s CRC in the file name.

Of course, this technique is not specific to CRC-32; it generalizes to CRCs with generator polynomials of any degree \(m\).

The algorithm described above has an excellent time complexity of \(O(\log (n-k))\) thanks to exponentiation by squaring. This means for any practical file size, the algorithm computes the modification in less than a millisecond. But the program still needs to read the entire file to find the original CRC-32, and to reread the whole file after modification to verify its correctness. (We assume that the generator polynomial is fixed, because the algorithm does become slower with higher degree polynomials.)

The derivation ignores the fact that the remainder is XOR’d by 0xFFFFFFFF afterward, but this is okay because we work with the delta that needs to be applied to the message and remainder.

One easier alternative algorithm, which doesn’t involve polynomial modular arithmetic, is to create the CRC delta and then operate the shift register in reverse. In this case, the minimum requirement for the generator polynomial (of degree \(m\)) is that the coefficient of \(x^m\) and \(x^0\) are both 1. The generator polynomial doesn’t need to create a finite field.

Another, more general alternative is to view it as solving a system of linear equations in \(\text{GF}(2)\). This works because each bit position in the message causes a specific delta in the CRC, so the problem becomes finding a linear combination of individual deltas to achieve the desired overall delta. Also, this approach is helpful for less-than-ideal situations such as modifying non-consecutive message bits, or having an under-determined system of equations that allows multiple solutions.

Elsewhere on the web, this technique is known as reversing a CRC or hacking a CRC. A Google web search for these terms will reveal similar work from other authors.

[0]: The generator polynomial for the most popular flavor of CRC-32 (for Ethernet, ZIP, etc.) is \(x^{32} + x^{26} + x^{23} + x^{22} + x^{16} + x^{12} + x^{11} + x^{10} + x^8 + x^7 + x^5 + x^4 + x^2 + x^1 + x^0\).

[1]: If the generator polynomial is irreducible in \(\text{GF}(2)\), then it defines a finite field. This is usually the case for the generator polynomials used in practice. When we have a field, the analysis is easier since every non-zero element has a multiplicative inverse. But forcing CRCs is still sometimes possible in polynomial rings.

More info

- Wikipedia: Cyclic redundancy check

- GitHub: resilar - crchack: Reversing CRC for fun and profit

- Greg Cook: CRC RevEng: arbitrary-precision CRC calculator and algorithm finder

- Google search: reversing CRC

- Sunshine’s Homepage: Understanding CRC

- Ross N. Williams: A painless guide to CRC error detection algorithms