Designing better file organization around tags, not hierarchies

Designing better file organization around tags, not hierarchies

Introduction

Computer users organize their files into folders because that is the primary tool offered by operating systems. But applying this standard hierarchical model to my own files, I began to notice shortcomings of this paradigm over the years. At the same time, I used some other information systems not based on hierarchical path names, and they turned out to solve a number of problems. I propose a new way of organizing files based on tagging, and describe the features and consequences of this method in detail.

Speaking personally, I’m fed up with HFSes, on Windows, Linux, and online storage alike. I struggled with file organization for just over a decade before finally writing this article to describe problems and solutions. Life would be easier if I could tolerate the limitations of hierarchical organization, or at least if the new proposal can fit on top of existing HFSes. But fundamentally, there is a mismatch between the narrowness of hierarchies and the rich structure of human knowledge, and the proposed system will not presuppose the features of HFSes. I wish to solicit public feedback on these ideas, and end up with a design plan that I can implement to solve the problems I already have today.

This article is more of a brainstorm than a prescriptive formula. I begin by illustrating how hierarchies fall short on real-life problems, and how existing alternative systems like Git and Danbooru bypass HFS problems to deliver a better user experience. Then I describe a step-by-step model, starting from basic primitives, of a proposed file organization system that includes a number of desirable features by design. Finally, I present some open questions on aspects of the proposal where I’m unsure of the right answer.

I welcome any feedback about anything written here, especially regarding errors, omissions, and alternatives. For example, I might have missed helpful features of traditional HFSes. I know I haven’t read about or tested every alternative file system out there. I know that my proposed file organization scheme might have issues with conceptual and computational complexity, be too general or not expressive enough, or fail to offer a useful feature. And certainly, I don’t know all the ramifications of the proposed system if it gets implemented, on aspects ranging from security to sharing to networks. But I try my best to present tangible ideas as a start toward designing a better system. And ultimately, I want to implement such a proposed file system so that I can store and find my data sanely.

In the arguments presented below, I care most about the data model and less about implementation details. For example in HFSes, I focus on the fact that the file system consists of a tree of labeled edges with file content at the leaves; I ignore details about inodes, journaling, defragmentation, permissions, etc. For example in my proposal, I care about what data each file should store and what each field means; I assert that querying over all files in the file system is possible but don’t go into detail about how to do it efficiently. Also, the term “file system” can mean many things – it could be just a model of what data is stored (e.g. directories and files), or an abstract API of possible commands (e.g. mkdir(), walk(), open(), etc.), or it could refer to a full-blown implementation like NTFS with all its idiosyncratic features and characteristics. When I critique hierarchical file systems, I am mostly commenting at the data model level – regardless of the implementation flavor (ext4, HFS+, etc.). When I propose a new way of organizing files, I am mainly designing the data model, and leaving the implementation details for later work.

Contents

The most important sections are denoted in bold. The other sections provide additional context for interested readers.

- Introduction

- Hierarchical file systems are useful

- Hierarchical organization is clumsy

- Alternative systems as inspirational examples

- Designing a tag-based file system

- Open questions

- Miscellaneous notes

Hierarchical file systems are useful

Hierarchies are popular because they serve a useful purpose. They do organize files to a certain extent, and are better than having nothing at all. (Older computer systems simply had a flat file system where every file is stored in the root directory of a drive.)

- Physical storage analogy

-

HFSes imitate how information is stored in the physical world. If you have a set of papers, you’d put them into a labeled folder, folders into a filing cabinet, cabinets into aisles, aisles into rooms, rooms into buildings, and so forth. Each piece of paper is stored in only one place, which can be described by a unique address. The content on a sheet of paper can be updated and the page can be stored back in the same place.

- Ubiquitous availability

-

HFSes are already available on every major computing platform – Unix (ext, XFS, ZFS, etc.), Windows (FAT, NTFS, ReFS), macOS (HFS+), Android, and web services (Dropbox, OneDrive, etc.). As a user or a developer, if you need hierarchical file organization, you will almost certainly get it.

- Reducing repetition

-

Instead of labeling each relevant file with a particular aspect, you group the files together and put them all in one folder named with the aspect. For example instead of writing “Bicycle” within each file name among a set of photos, you can put those files into a folder named “Bicycle” and not need to touch the individual file names.

- Filtering out items

-

Browsing a hierarchy is powerful because it inherently filters out unwanted information and brings wanted information to the forefront. For example when you open a folder called “Tax Documents”, you will not see the party photos which are stored elsewhere.

- Naturally hierarchical phenomena

-

Some natural concepts have a nested structure and are already labeled in a hierarchical way. Geographic locations are hierarchical – a city belongs to a state which belongs to a country which belongs to a continent. For example if you want to organize a set of travel photos, you can make a folder for each country, a subfolder for each city, and so on. Each photo belongs to only one place, never two countries or two cities at once. Divisions of time are hierarchical. You can create a folder for each year, and put each document in one year folder. Or you can go finer and create a subfolder for each month, et cetera.

- Simple implementation

-

Hierarchical file systems are relatively easy for an operating system designer to implement, compared to fancy relational databases or such. At their core, HFSes involve rooted trees (or directed acyclic graphs), node pointers, edge labels (directory entry names), and file blobs. Writing user-level applications that operate in a hierarchical file system is quite manageable too. A simple program might just work on single files, or list a directory non-recursively. Even in the full case of walking over files and directories recursively, the data model is simple and easy to work with.

Another benefit is that data retrieval can be fast in practice even when directories are stored on disk naively as unsorted lists (without applying advanced data structures like B-trees). This is because users are naturally inclined to keep the number of items in a directory at a manageable number – if a user sees a directory with a thousand items, she will likely create a few subfolders and put a few hundred items into each. This benefit of fast linear searching does not apply to flat file systems, where a root directory might have tens of thousands of files (thus B-trees must be used, but flat file systems are obsolete anyway).

Hierarchical organization is clumsy

With the benefits of hierarchical file systems out of the way, let’s discuss how they seriously fall short in helping us organize files – or more broadly speaking, how they represent and retrieve knowledge. A tricky aspect about the upcoming arguments is that HFSes appear to behave okay at the small scale (say 100 to 1000 files), but they become increasingly painful to use at the large scale (say 100 000 files).

- Forced unique names

-

Every file within a folder must have a unique name. (Or phrased more formally: For each directory in the file system, each item in that directory has a name different from all other items in that directory.) This seems like a reasonable design on the surface – after all, you need some way to identify and access each file – but its implications are troubling.

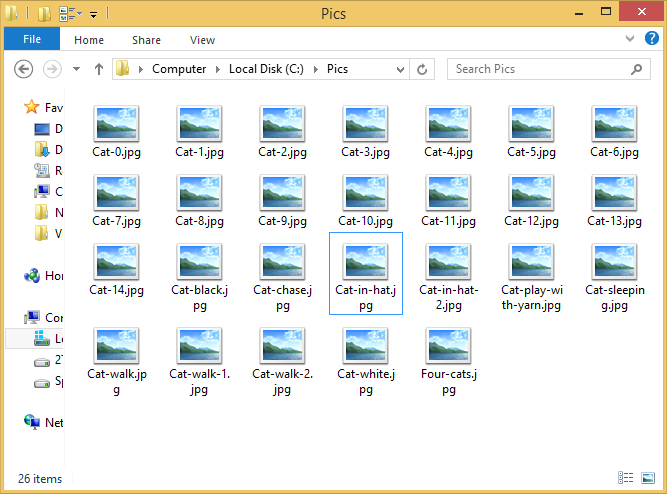

Example: You browse the web and download a bunch of cat pictures one by one. You just want to name every file “Cat.jpg” because it’s the best description you can think of without spending extra mental effort. But saving them into the same folder, each file needs a unique name. So you might decide to append a number to them, like “Cat-0.jpg”, “Cat-1.jpg”, “Cat-2.jpg”, etc. – fine. Or you might start to describe each one in more detail, like “Cat-in-hat.jpg”, “Cat-sleeping.jpg”, “Cat-chase.jpg”. But eventually you will see a picture that deserves the same description, so you’ll still end up with numbered names like “Cat-in-hat-2.jpg”, etc. Either way, once you start numbering files, you need to check the highest existing number every time you save a file. This procedure increases mental burden without actually improving the information being stored – it merely works around the unique name requirement imposed by the system.

Example: You do a photoshoot and capture a series of images, say “Fred-01.jpg”, “Fred-02.jpg”, ..., “Fred-30.jpg”. You delete some outtakes, leaving holes in the sequential file numbering. If you publish this subset of photos as is, the consumer might wonder why there are gaps in the numbering, and get unintended insight into how many raws were shot. But it gets worse – your coworker Mary was shooting alongside you, and offers you her collection of photos of the same subject. In a stroke of bad luck (or great minds thinking alike?), she also named her photos “Fred-01.jpg”, “Fred-02.jpg”, ..., “Fred-19.jpg”. You want the benefit of being able to use her files, but now you are left with a dilemma on how to organize them. You can either put her files in a separate folder so that you end up with “Me/Fred-01.jpg” vs. “Mary/Fred-01.jpg”, or you can re-number her files to integrate them into your collection (e.g. add 30 to Mary’s numbers), or you can add a prefix to her files (e.g. “Mary-Fred-01.jpg”) and put them into your folder. The first option of keeping collections in separate folders is the easiest to do but makes retrieval awkward; the second and third are awkward due to poor tools for renaming files, and have a high potential for human error (misnaming, accidentally deleting, or overwriting files). In all cases, you have to take extraneous actions to merge two collections together or retrieve files from a merged collection. These extra steps stem from the hierarchical filing paradigm, not from the idea of merging data.

The requirement of unique file names is motivated by the need to make file paths meaningful. An absolute path starting from the file system root, like “/abc/def/ghi.png”, should be traversed in only one way and lead to one (or zero) files. If any component of the path is ambiguous – say there are two items named “abc” in the root directory – then the result could be a set of one or more files. Applications programs are just not designed to deal with this situation; it is a fundamental design assumption in HFSes that each path represents either zero or one file, and this behavior can’t be changed without breaking millions of existing programs. Having unique, meaningful, practical paths is a laudable goal. But asking end users to directly create unique file names and manage such a collection over time seems to cause continual low-level pain.

Any file organization system that allows random access to files must have a set of unique names (whether meaningful text or random garbage) in some form or another. One solution implemented in various software systems is to let the computer generate unique file names. For example when you upload a file to 4chan (image board website), the server saves it with the name set to the current Unix millisecond timestamp (e.g. 1487783267847.gif). Unfortunately this simple-sounding scheme requires a great deal of care to implement correctly. The server could be unlucky and process two requests in the same millisecond, so it would need to keep track of the last issued timestamp and use a new number that is strictly greater. If the site continually handles more than 1000 uploads per second, then the naming scheme must be changed. If the server is part of a cluster, then they need to communicate with each other to avoid reusing file names already issued by other servers. A much more reliable alternative is to name each file by the hash of its byte-level content, for example the SHA-256 hash value of 87529003

f42c1f04 39b0c760 ebfe5e6d ff1b436c 3c9b4f8b 41ad9b1f e6dc6795 (64 digits). Hashes are long and ugly, but have a couple of useful properties in this situation. The same file content always produces the same hash (unlike the timestamping scheme), so exact duplicates are easily detected. No communication or coordination is needed among a cluster of servers, because probability theory ensures that these random-looking names are extremely unlikely to collide. Hence it may not be desirable or necessary to let the end user choose and manage unique file names. As we’ll see later, it might be a good idea to design a system where each file name is an auto-generated hash, but where files can be named, categorized, and queried using higher-level metadata systems.

- One and only one classification

-

File names and paths in a hierarchical file system serve double duty: they tell the machine how to reach a file to in order to retrieve it, and they show the human how the file is classified. This conflated design seems reasonable at first, but hinders efforts to classify a file in more flexible ways.

Example: You have a folder named “School” for all the documents and files related to school activities. You have a folder named “Photos” where you store thousands of pics taken over years. Now you take a couple of photos of activities in volleyball club. Where should you store these photos? They could go under “School”, “School/

Photos”, or “School/ Volleyball-club/ Photos”, but you could also argue that you want to be able to find the photos in your general life stream, so they could be filed under “Photos” or “Photos/ Volleyball-club”. If you store the photos somewhere under the “School” folder, then your general photo album will be incomplete. Worse, if you wanted to recall a particular photo but forgot that it was stored in the “School” folder, then you are out of luck when browsing the “Photos” folder. You could copy the files and store them in both locations, but that wastes space and could lead to future problems when you need to rename or reclassify things. Example: Your primary music collection has a few hundred albums in lossless quality FLAC. You decided to re-encode all the audio files to the much smaller 128-Kb/s MP3 format as a new parallel collection, because you want to store music on small flash cards or stream them over the Internet. But now you face an organization problem: Do you store the MP3 files alongside the FLACs, or do you store them in a separate hierarchy? Namely, would you make a folder structure like “My-music/

Album-name/ MP3/ Track-01.mp3” or “My-music/ MP3/ Album-name/ Track-01.mp3”? There are good reasons to argue both ways. If the album name is nearer to the root of the hierarchy, you can see all the audio files pertaining to a particular album. But maybe on the computer you only care about the FLAC files, and the MP3 files are a distraction so you ignore them most of the time. With the separate top-level folder for MP3s, it is easy to ignore all the FLAC files or ignore all the MP3 files once you go into the appropriate folder. But then it becomes hard to keep your albums in sync – how do you check that every FLAC album has been encoded to MP3? And if you deleted a FLAC album, how do you know that you need to go and delete the MP3 album to match? This example only involves two attributes. It only gets worse as you add more classification axes – like grouping albums together by artist, or sorting music by year of release. You will agonize over whether the correct hierarchical classification is “My-music/ Artist/ Year/ Album/ Format” or “My-music/ Format/ Year/ Artist/ Album” or “My-music/ Year/ Artist/ Album/ Format” or the numerous other permutations, when in fact all of them have equal claim in being a correct classification. - Focusing on path, not content

-

In hierarchical file systems, the path to a file tells us how to retrieve it, not what is inside the file. For example, “/home/

john/ diary.txt” tells the computer to start from the root, go into the directory named “home”, go into the subdirectory named “john”, and follow the link named “diary.txt” to access the file. It doesn’t necessarily tell us anything about what the file contains – for all we know, it could be an actual diary or a downloaded movie. To make matters worse, the meaning of the path is relative to which computer system we’re working on. The same path “/home/ john/ diary.txt” might exist on a distant server, but possess completely different file content. It turns out that the notions of storage location and arbitrary content are not inherent properties of file identifier strings. We can, and have designed systems where the file name reflects what the file actually contains, and moreover such file names are globally unique (thus location is unimportant). The best example comes from Git version control: Given a 40-hex-digit object hash like d5a20366

d5d5d0fc 5ae4350c fd65ba7c d599b6bc, there is at most one (practically computable) sequence of bytes that produces this hash; when you receive the full file you can check it against the hash. Furthermore, the global uniqueness means that it is redundant to talk about “my variation on the file d5a2...b6bc” or “your hosted copy of d5a2...b6bc”; the hash name has one meaning everywhere. Therefore regardless of whether you received a copy of the file d5a2...b6bc from GitHub or from Bitbucket, from Bob’s project or from Carol’s project, it is always identical. In Git, the name of a file describes what it contains, not where to find it. (Slight caveat: This article was written just a week before the first SHA-1 collision was publicly announced.) - Hard and soft links as non-solutions

-

When people realize they need to classify a file in more than one way, they will start to use shortcuts/links to try to solve the problem. (Windows has shortcuts, Unix has soft/symbolic links, and Mac has aliases. This is a ubiquitous feature, but transferring shortcuts across existing platforms is very hard.) This sounds like a reasonable solution, but will face trouble in all but the simplest use cases.

Example: Going back to the school photo scenario, you might decide to store the actual files in “Photos”, and create a set of shortcuts in “School/

Photos”. Fine for the time being. Example: Going back to the music classification scenario, you might decide that you like multiple ways of classifying your music. So you set up three separate hierarchies, like “My-music/

Artist/ Year/ Album/ Format” and “My-music/ Format/ Year/ Artist/ Album” and “My-music/ Year/ Artist/ Album/ Format”. You begin by filing each music file into one of these hierarchy schemes, and then create hard links in the other two hierarchies. In this case, there is no distinction between the primary copy and aliases; all three hierarchies have first-class hard links to the underlying files. (This Unix & Linux Stack Exchange answer describes this scheme.) Now to discuss the problems. Hard links only work within a single file system, so you can’t link between files stored on two separate non-RAIDed hard drives – but in exchange, hard links never have problems when some of the links are renamed or moved. Working with hard links requires a great deal of care – when copying or backing up an entire directory tree, you want to preserve the hard link structure to avoid duplication and to keep the behavior when shared files are edited; when reclassifying files you need to pay special attention not to delete the last hard link to a file.

Soft links have a nearly opposite set of problems as hard links – soft links can span different file systems, but they generally don’t track the target files getting moved or renamed (except that Windows provides such a system service, but may not be reliable); while hard links are all indistinguishable, some application software behaves differently on soft links than on real hard-linked files.

In addition to these problems, hard and soft links require an exponential amount of effort to classify a set of files in multiple ways, and require the user to manually remember all the possible paths that a file can be reached from (important when editing and removing files, not important when browsing/

retrieving files). They are non-scalable kludges compared to true tagging. When a program’s logic is written without an awareness of file links, it is usually no problem for the program to read a file/

directory through a hard or soft link. But using such an unaware program to write items through a link can lead to confusing behavior and even data loss. This happened with the Dropbox file synchronization utility and is described in an article by Aurelio Jargas and in an article by Paul Ingraham. - Mutability as a liability

-

By default, all files in a hierarchical file system are mutable (a.k.a. editable, writable). This makes a lot of sense because some notion of file system mutability is required to get any work done at all. Also, because the paths pointing to a file stay the same even after it is edited, there is no ambiguity about what it means to edit a file. These factors together allow a usable file system to be implemented with low complexity.

Again, while mutability seems reasonable on the surface, it creates problems at the large scale. The freedom to modify any file hurts when files need to be compared, backed up, shared, synchronized, or referenced. The basic problem is that when given two file paths, say “/path/to/a.txt” and “/path/to/b.txt” (or more generally paths to two trees), the only way to reliably determine whether they have identical content is to read both files fully and compare every byte (unless the file system caches the full content hashes, which I think no file system does). So if two different people email you a document named “Project Proposal.doc”, you cannot tell at a glance whether they are the same or different just by looking at their names. If you have a collection of work files on your desktop, which you transfer to your laptop, then you edited a few files on your laptop, you cannot easily tell which files have been edited.

Sometimes you want to archive a set of files and be very careful to never edit or delete them. For example you might consider all the photos you shot to be an append-only collection, and you might choose to preserve some draft stages of a document you’re editing. HFSes have a partial solution to this problem, which is to disable writing for a file (Unix style) or set the read-only flag for the file (Windows style). But it is still easy to accidentally disturb the supposedly archival files. If a folder contains archival and non-archival files at the same time (such as live documents alongside draft snapshots), then you might forget this fact and accidentally move or delete the directory in such a way that violates your intent.

Having file paths that refer to mutable blobs of data isn’t the only way to design a file system. An alternative idea is to force the name to change every time a file’s content changes. Hashing is one mechanism that satisfies this property. (Generating a new random name every time a file is edited is also possible, but it has fewer desirable properties than hashing.)

- Difficult backups and caches

-

Hierarchical file systems provide no help in keeping track of how many copies you own of a particular a file or set of files. A special case of this statement is that you can’t tell if a file (or set of files) is new / freshly edited and has not been backed up at all (i.e. only one copy available, no extras).

Example: You have a single folder containing several gigabytes of videos, stored on your computer’s internal hard drive, which you wish to back up. You go and buy an external disk, plug it in, and copy the entire videos folder from your internal drive to the external drive – simple and easy to understand. Now you update your primary video collection by adding new files and editing a few. You want to update your backup to match, but what should you do? The simplest (and least error-prone) approach is to ignore the existing backup and add a new complete copy of your current folder; you may choose to delete the existing backup. This approach is wasteful in storage space and I/O transfer time; it works if the collection of files is small but becomes impractical if the total file size approaches the storage size (for example having 400 GB of data when you can only afford to buy a 500 GB backup drive). So you adopt an incremental backup strategy, where you only copy/manipulate files that have changed. We know that in general, it is impossible to tell if two file paths have the same content without fully reading both files. An incremental backup program would probably use the heuristic of checking file sizes, timestamps, and archive bits to see if a file needs to be re-copied. The heuristic works well in practice, but can still be subverted by accident (by a well-meaning tool that forges timestamps) or by malice. By changing some file content without changing its size or timestamp, it is possible that an incremental backup program does not copy the actually changed file to the backup storage for an arbitrarily long time.

Example: You keep the primary copy of all your files on your desktop computer, but copy a few files (such as books and movies) to your laptop for temporary use. You want to mark the files on your laptop as cached copies, so you put them into a folder named “Cached”. The idea is that it is safe to delete any file in the “Cached” directory or the whole directory at any time. But you have to be extremely careful to never add a non-cached file to it (such as a newly edited document), never directly modify any files in the cached directory, and never modify one of the files on your desktop without updating the laptop cache.

As we can see, the idea of mutable files quickly changes from a convenience to a liability, and the file system does nothing to help us keep track of file changes or duplicate copies. All this adds up to mental tracking effort and human overhead for things that the computer should take care of for us.

As far as my own policies go, I trust neither the primary copy, the backup(s), nor myself. For example before I delete a set of backup files, I want to check that each file still exists somewhere in the primary copy and has identical content – this protects against corruption or unnoticed accidental deletion in the primary copy. For example when I make an incremental update to an existing backup, I want to make sure that after the update finishes, the entire set of backup files contains exactly the same content as the primary copy, ignoring any excuses about timestamp and file size heuristics. In both cases, hierarchical file systems make it a laborious and error-prone process to verify identical file content and to detect the set of changed files.

-

A folder with many thousands of files in it is not easy to handle. Command line tools like

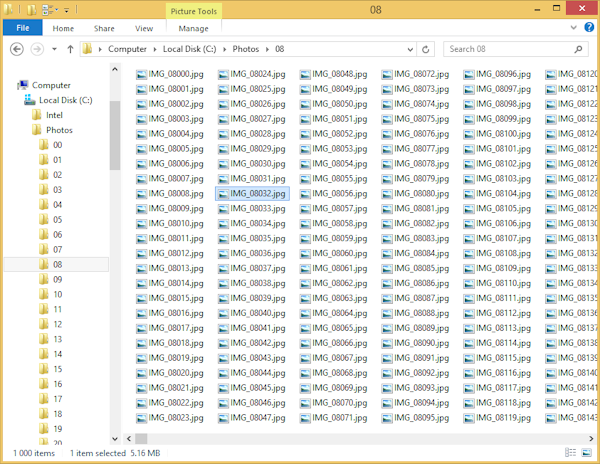

lswill handily overflow the screen with file names. Graphical tools like Windows Explorer might take a few seconds to load all the folder entries while the screen stays blank, and then you still have to scroll through the long list of files to find the one you want. Performance and usability are degraded because the system is designed around the assumption that you care about seeing the entire set of files in any particular folder, rather than presenting results incrementally. Because of this, when a normal user encounters a folder with a few thousand files in it, they are incentivized to create subfolders and move items into them to fix the undesirable behavior.For example because of this behavior on large folders, I am forced to split up my photo collection – somewhere in the order of 100 000 files – into chunks of 1000 for sane browsing. I created folders like “00” for the zeroth thousand items (000~999), “01” for the first thousand (1000~1999), “02” for the next thousand (2000~2999), and so on. But in theory, this is extra effort to artificially work around a dumb file system concept. I would be thrilled if I could dump all my photos into one giant folder, and let the system software figure out how to present subsets of that data in a responsive, performant way. It’s almost as though hierarchical file systems have forsaken some of the beauty of a flat file system.

Reorganizing a large folder is done not only by humans but also by automated tools. For example, Git stores loose objects in 256 directories (one for each initial byte value), each of which can contain an unlimited number of files (but in practice contains about 1 to 30 items). For example, Subversion’s FSFS repository format version 4+ (SVN tool version 1.6+) supports sharding so that 1000 revision files (instead of unlimited) are stored per directory. In both cases, the sharding logic is intended to work around potential poor performance in an HFS, but introduce complexity and do not improve the quality of the data being stored.

This point ties back to other observations about HFSes and human effort, such as the one about unique names. There is a running theme that HFSes have a simple data model and allow for simple implementations, but shove all the complexity to humans to manage manually.

- Overly rich file semantics

-

A “file” on a modern HFS is not a mere sequence of bytes; it comes with many pieces of extra information attached by default. General-purpose operating systems are designed for multiple users, hence each file has information about ownership and permissions (read/write/execute/etc.). A file may have special attributes like “append-only” or “cannot be moved or modified until the immutable flag is removed”. A file may be accessible from multiple paths due to hard links, which means that backup and restore tools must handle this case correctly to replicate the exact read/write behavior. A file has timestamps denoting its creation, last modification, and last access – but the former two are useless/misleading when a file is already tracked in a higher-level versioning system like Git, and the latter can be disabled to reduce I/O workload. On Windows, every time a file is modified its archive bit is set; when some backup program successfully archives the file the bit is cleared – but this presupposes that only one backup program can be responsible for managing a file. A sparse file can be created and only have some parts filled in, but why not design the file format to cope with data growth in the first place? A file can be locked by a process for exclusive access; moreover file locking and content sharing can provide a communication channel between processes. The Wikipedia pages on file attributes and the chattr tool illustrate just some of the numerous properties a file can have.

It is not a universal truth that files are treated as objects with many rich properties. For example in Git, a file is a sequence of bytes with a single unique path (within a commit), and only has the executable flag as an additional property; there are no other hidden attributes, permissions, etc. (Subversion, however, has many hidden attributes on a file, such as its merge history and a unique ID.)

Alternative systems as inspirational examples

- Git version control

-

Git is a popular tool in the software development community, which takes snapshots of a project’s hierarchy of directories and files. Inside the world of Git, every data object is addressable by a globally unique 160-bit (or 40 hex digit) SHA-1 hash value, regardless of whose repository it’s stored in. Some of these objects, called trees, have children labeled with ordinary file names. In essence, Git is a dual system with immutable hash-addressed objects as the primary retrieval mechanism, and hierarchical tree paths as a secondary (and incomplete) retrieval mechanism.

The notion of hash names in Git solves a number of problems by design. Suppose you and your friend halfway across the world both own an object with the hash e4d4634d

3d2b4fd3 5c11864b b00eb0d9 1b760c68 – in this case you can be sure that you both have the same file content, without needing to transfer every byte of a potentially large file. In another scenario, suppose you and your friend start at the exact same snapshot (commit), make some different changes, and each take a new snapshot. In other version control systems that use numbered revisions (e.g. rev 3, rev 4, rev 5 in Subversion/SVN), you can’t both claim to have created revision n+1 because one of you must have come first and the other come after. But Git makes these divergent changes possible because snapshots are labeled by hashes and hashes don’t have a sequential order – both of you will end up with a new commit object with different hashes, and this works fine in a model where the revision history is a directed acyclic graph rather than a straight line. The immutability of files in Git makes some HFS problems non-applicable. If you take a particular object, say the one with hash 0be5...0ee7 and change a few bytes of its content, then the new object will (with extremely high probability) have a different hash. The hash gets recorded in the tree and in turn affects the snapshot hash. It is practically impossible to accidentally or intentionally change a file in an undetected way; every change, no matter how small, will be detected by Git with statistical near-certainty. So if you wanted to compare a particular file tree against a backup copy, you can simply look at the hashes to reliably tell if any new data needs to be synchronized.

- Danbooru-style image boards

-

Danbooru, Gelbooru, Konachan, etc. (all NSFW) host millions of anime drawings that are categorized in multiple ways: by character, by appearance, by series, by author, et cetera. They offer these classifications without resorting to hierarchies, and instead rely on tagging. The data model works like this: Each uploaded image is saved with its MD5 hash as file name, and is also given a sequential serial number (e.g. #2638577) for compactness. Each image can have any number of tags attached, where each tag is a simple string; examples of tags include “hat”, “1girl”, “pink_hair”, “kantai_collection”, “izumi_konata”. When you open an image, the page also shows what tags are associated with that image. You can also query a tag and see the list of all images that have the tag. This two-sided query is a handy feature that hierarchical file systems are not designed to support. Note that other than the hash and serial number, each image doesn’t have a name in the traditional sense. No one forces you to name a set of images like “Nanoha 1.png”, “Nanoha 2.png”, “Nanoha 3.png”, etc. The list of tags is not required to be unique either (i.e. two different images can end up with the same tags), and in fact no tags are strictly required at all (but it would make the image rather difficult to retrieve). These concepts are a complete reversal of what we are accustomed to in hierarchical file systems.

The Danbooru image tagging system is actually richer than described so far, because tags are not just simple strings. Each tag has a type attribute, which can be either general, character, series, or artist – this makes it possible to distinguish between a tag for a fictional character named Yuki versus an artist named Yuki. Moreover each tag has a description page attached to it, allowing more information to be added to explain what the tag means (e.g. defining the term zettai ryouiki and setting the judgement criteria).

Once upon a time I tried to curate a set of anime images on a local hierarchical file system, but failed to maintain good organization as the number of files grew. I kept running into the problems of unique file names and single classification. The existence of Danbooru confirmed to me that HFSes are a lost cause and it is futile to continue working under the hierarchical model.

Flickr (SFW) is a photo sharing site where photos can be classified/retrieved by tags like on Danbooru, but also by primary color, full text search, geographic location, and copyright licensing. However, I chose Danbooru as the primary example because tag browsing is a mandatory part of the user experience, whereas Flickr has fewer tags per photo and more emphasizes browsing by author instead of by tag.

- Relational database model

-

The relational model along with RDBMS software is a popular and powerful way to store and access data. Relational databases power many web services and company-internal services alike. The relational data model, how to design tables, and how to design queries are all taught to novice programmers and are well known in the industry, so I will not explain their background concepts.

Relational databases are strictly more expressive than hierarchical file systems; you can emulate an HFS through an RDBMS, and still have room left over to add non-hierarchical features like cyclic references. The data model of the Danbooru image board can easily be reverse-engineered as a set of tables:

- Images: int imageId (primary), byte[16] md5Hash, byte[] fileData.

- ImageTags: int imageId (foreign), int tagId (foreign).

- Tags: int tagId (primary), string name, int type, string description.

- Comments: int imageId (foreign), int sequence, string message.

As we will see later, the file organization system I will propose will be a different way of phrasing the relational model.

- Music libraries

-

When I mention the example of how HFSes fail at music organization, most people will give a confused look because their favorite media player has a built-in library to manage the metadata and queries. For example, the software music players foobar2000, Winamp, Windows Media Player, and iTunes all have a music library as a feature. To choose a song (or songs) to play, users can either use their system-level file manager (Explorer, Finder, etc.) or use the library UI within the media player program. A music library can be viewed as a table with one row per song and one column per attribute (title, artist, album, length, rating, format, etc.). By default, the music library shows every song that a user is known to own. Then one can sort and filter on arbitrary columns – for example searching Hamasaki Ayumi as the artist, examining the results, then further narrowing it to ratings of 4+ stars. The ability to search and filter results in flexible ways is light years ahead of what a hierarchical file system alone can provide, and takes far less effort both when storing songs (no need to create multiple crazy hierarchies) and when retrieving songs (no need to navigate down a tree of folders).

A major problem with music libraries and file libraries in general is that they are proprietary and narrow. It can be taken for granted that foobar2000 and Winamp will track your music collection separately – so any changes made to one library need to be manually performed in the other library. A file library can hold facts about your music collection that are not stored in the music files themselves, such as rating or play count, but be difficult to export to an open format (e.g. CSV text file). As for narrowness, a similar concept applies to photo libraries. Adobe Lightroom, and probably many other photo editing/catalog software, maintains a library of all the photos you own, no matter where on disk they are stored. The library allows queries like by date, by camera, by rating, by text tags, etc. But again they are data silos and interact poorly with the outside world.

Media libraries are wonderful and have shown us how powerful and practical they are. But their limitations suggest that we should design a system where media libraries are universal (applies to any file), singular (so all music player software on a computer will share the same library), and trivial (so an application developer relies on the system-level media library instead of developing his own from scratch).

- InterPlanetary File System (IPFS)

-

The IPFS project aims to solve some of the same file organization problems that I have. IPFS gives every file a unique fingerprint (i.e. hash), detects duplication, tracks version history, provides decentralized search and distribution, allows machine-readable links within files, and much more. I picked up a few helpful ideas from reading their whitepaper, but acknowledge that many of their goals don’t correspond to mine. IPFS seems to describe at length about their DHT-like decentralized directory service and how nodes connect to each other, whereas I only care about how data is represented/modeled. IPFS allows a file to be composed of a list of raw blocks of byte sequences, a complexity motivated by documents that get edited over time. They propose supporting mutable files via path strings that contain public keys, which seems questionable at best and detrimental for archival at worst.

- Tuple spaces

-

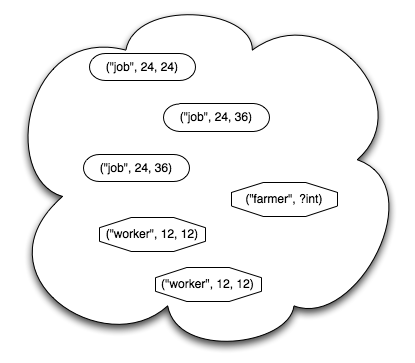

The model of tuple spaces comes from the world of parallel computing, not file storage and distribution. The idea is that every fact we might want to express is represented as a tuple of values, such as (“Kevin”, 32, “Paris”). Tuples have no path or label; they are pure values. Tuples can be stored, queried, and retrieved from a pool. If the pool is accessible by multiple processors/computers, then this becomes a way to communicate data between them. In a sense, if you take a database, examine all its tables, and make every row into a tuple floating in space, then a tuple space is what you end up with. This abstract and overly flexible idea of a tuple space will form the basis of the file organization system I describe later below. There is a lack of good descriptions of tuple spaces, but a blog post at Software Carpentry paints a decent picture.

-

-

experiments in space in formation: Alternatives to hierarchical file systems (1 page)

A short post that echoes my thoughts about paths, tags, and multiple classification. -

A novel idea for a new Filesystem: Storing facets as key-value pairs for individual files (7 pages)

Identifies a number of limitations and pain points of hierarchical file systems clearly. -

Hierarchical File Systems are Dead (5 pages) (discussion on Hacker News)

Short paper that covers problems in HFSes like over-emphasis on storage location and only allowing a single categorization per file, and proposes a data model (with diagrams) along with an implementation sketch. -

TagFS: A simple tag-based filesystem (10 pages)

Presents ~15 API functions to illustrate what the system provides. Describes unions of data sources, Boolean queries, and query optimization. Advocates the use of semantic triples in tags. Talks about modifying existing hierarchical-path-based applications to fit this system. -

Going beyond the hierarchical file system: a new approach to document storage and retrieval (6 pages)

A paper highlighting the fact that classifying a file along multiple axes is poorly modeled with hierarchies. Also shows their proposed user interface for saving, tagging, and querying files. -

TagFS — Tag Semantics for Hierarchical File Systems (6 pages)

Illustrates how to shoehorn a tag query system into a virtual legacy hierarchy that is served over the WebDAV protocol. -

Improving the Usability of the Hierarchical File System (10 pages)

Identifies the relationship between classifying files and storing values in a database table. -

How-To Geek: Zen and the Art of File and Folder Organization (~40 pages)

An earnest but ultimately doomed attempt to teach users how to organize files into folders, and to create shortcuts in secondary locations. -

Control-Alt-Backspace: Filesystem Links: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know (~10 pages)

Explains the behavior and creation of hard and soft links on multiple operating systems. -

The Lifestreams Software Architecture (185 pages)

Comprehensively designs and tests a system for workflow and archival, based on chronological presentation plus keyword and attribute filtering. -

The Science of Managing Our Digital Stuff (book, 300 pages)

Compares hierarchies/folders, search, tagging, and team/shared spaces. Discusses user studies where they measure human performance, and repeatedly advocates hierarchical navigation. A talk video (65 minutes) covers part of the book’s content. -

Representing Information About Files (8 pages)

Proposes a model of metadata attributes, indexing and querying of metadata values, and file versioning – for files stored in a classic hierarchy. The sequel is a dissertation (204 pages; table of contents near last page). -

Wikipedia: WinFS (~15 pages)

The ultimate vaporware file storage project, with lofty goals to support rich metadata and queries, but was perpetually delayed and then cancelled. A series of four blog posts talk about how WinFS was designed intended to organize information. An interview video (58 minutes) provides another rather detailed view of the design goals, and shows several demos of the prototype system’s functionality. - More Wikipedia: Object storage, Digital asset management, Semantic file system

-

experiments in space in formation: Alternatives to hierarchical file systems (1 page)

-

-

Perkeep (formerly Camlistore)

Lets you store, organize, and access data on your own computer in Perkeep’s format. Provides a command line interface and web interface for access. Fairly fleshed out in terms of functionality. See their documentation section for a project overview and presentations. - Tagsistant: semantic filesystem for Linux

- Tabbles: File Tagging, Document Management

- TMSU (Tag My Shit Up)

- Another proposed hash function transition plan - The Keccak Team

-

Perkeep (formerly Camlistore)

Designing a tag-based file system

Let’s demolish all the assumptions and baggage from modern hierarchical file systems and start with a fresh slate. Step by step, we will build up a data model for what I think is a reasonable way to organize files. This plan is not final at all, and I enjoy intellectual discussions on shortcomings and hearing better ideas. We will talk in the abstract and not worry too much about implementation feasibility at the moment; just assume that all data retrieval queries can be answered by performing a brute-force linear scan of all objects in a collection.

- Immutable file objects with hash identities

-

Define a “file” to be an immutable, finite sequence of bytes. In other words, a file is a list of numbers, and changing the length or any number produces a new file. A file has no name, no location, no attributes attached (timestamps, permissions, etc.), and no hidden semantics. You can picture a file as a block of numbers floating in space among other files. Define the “hash” of a file to be the SHA-256 hash of said sequence of bytes. Note that each file maps to exactly one hash; there is no ambiguity in how a file gets hashed.

Although SHA-256 is just one possible hash function we can use, it satisfies a number of useful properties, such as:

Every hash value is the same length, namely 32 bytes long. (Variable-length hashes would be an unnecessary pain to work with.)

It is extremely hard to find two different files with the same hash value. (Collision resistance; this means it is extremely likely that every file we ever produce will have a different hash.)

Given a particular hash where we don’t already know a file that produces it, it is hard to create a file that produces the hash. (Preimage resistance; this means we can’t just see a hash and forge a file that satisfies the hash.)

Given a particular file, it is hard to create a different file that produces the same hash. (Second preimage resistance; this means it is hard to substitute a different file that passes a hash check.)

At this point, assume that our file system stores an unordered, unnamed set of files (byte sequences). Furthermore, assume that if the system is given a hash, then it either locates the file possessing that hash or returns nothing. An API sketch of this hypothetical file system looks like this:

void addFile(byte[] b)bool containsFile(Sha256 h)void removeFile(Sha256 h)byte[] getFile(Sha256 h)Sha256[] getHashesOfAllFiles()byte[][] getAllFiles()

Notice in particular that no file has a name or any tag associated with it, and no file can be changed in place (but you can remove a file, change the content in memory, and add a different file). Now based on those low-level file system operations, we can define an overwhelmingly powerful function:

Sha256[] queryFiles(Predicate p)

This evaluates a predicate over every file in the whole collection, and returns the set of hashes of all files that match. In this context, a predicate has a single function

bool check(byte[] file, byte[][] allFiles)that decides whether any particular file belongs in the set of results. For example, a simple predicate might be “file is longer than 1000 bytes”, or “the first 4 bytes of file are 0x66 0x4C 0x61 0x43”. The general predicate also receives the set of all known files because then it can test whether some other file makes a reference to the current file being examined. Although arbitrary predicate functions will require a full scan of the file system and expend CPU time and I/O resources, later we will work with one useful predicate that covers many use cases. The predicate is “does some file G contain a hash reference to F?”, which allows precomputation and indexing. -

Here, tags will largely replace the role of folders and file names in traditional HFSes. We shall define a tag as a file containing two fields: (string name, Sha256 target).

Example: We have a photo with the SHA-256 hash of dc0e1601

3b70816b 6d124163 1fe569c1 e47b187f 781f929a 066508b4 9d4e3d98 and we wish to describe it with tags. So we can add a bunch of tag files to the nebulous file system pool, like (“photo”, dc0e...3d98), (“Africa”, dc0e...3d98), (“sunset”, dc0e...3d98), (“2003”, dc0e...3d98). It may seem verbose to write the hash of the photo each time, but this simplifies things later on and lets us continue to keep the system flexible. Furthermore, for personal collections this bit of text doesn’t take up much space compared to bulk media files, and there are strategies to store the data in a more compact way while still maintaining the same conceptual model (discussed later). Remember that tags are not file names. A file can have no tags at all. A tag like “dog” could be applied to 5 files (with no sense of “uniqueness” like “dog 1”, “dog 2”, etc.). Simple tags are a great start; they provide an expressive system for classifying files and already liberate us from all the constraints of hierarchies and unique names.

Suppose we can query the file system by tag, with an API like this:

Sha256[] getFilesByTag(string tagName)Sha256[] getTagsByFile(Sha256 h)

Note that these are special cases of

Sha256[] queryFiles(Predicate p)mentioned earlier.When it comes time to access our files, we have the freedom to choose any tag to find a file. For example we might query the tag “Africa”, which returns a bunch of photos, videos, and travel documents. Or we might start with the tag query “photo”, and get back photos depicting Africa, Germany, and school. Moreover, note that tag search results are inclusive whereas folders force us to dig down until there are no more subfolders. In an HFS we might have a path like /Photos/Germany/Berlin/Emily.jpg. The problem is that if we are browsing at the level of /Photos/Germany, we don’t even see all the descendant items such as the photos within the Berlin folder. This is a non-problem in tag-based systems because a photo can be classified as Germany and Berlin simultaneously, and you only need to match one tag, not necessarily all the tags, to find a particular file.

-

Simple tags are easy to understand and I believe offer enough functionality for the average user. But simple tags have a number of limitations:

Renaming a tag is highly disruptive. For example the city of Edo changed its name to Tokyo. If you have a bunch of files tagged with the string “Edo”, then you need to read each tag file, create a new tag with the new name but same target, add the new tag file, and delete the old tag file.

Some names are ambiguous and represent multiple distinct concepts. The word “chat” means something different in English than in French. What are you going to do, disambiguate them as “chat (English)” vs. “chat (Français)”? What if you spoke English all your life and didn’t know that the word collides with French? Other examples post-disambiguation include “Apple (company)” vs. “apple (fruit)”, and “Toronto, Ontario, Canada” vs. “Toronto, Ohio, USA”. But some names are very difficult to disambiguate, such as two different people named “John Smith” – what are you going to do, call them John 1 and John 2, or add social security numbers or birth dates to people’s names?

Tag strings are language-centric, even though what we really care about is the underlying abstract concept. For example you might tag a bunch of photos as “Canada”. Why not tag them as (Chinese) “加拿大” instead?

Some concepts have multiple, inconsistent, and/or disputed names and spellings. It ranges from terms like email / e-mail / electronic mail, to country names, to old and new ways of transliterating foreign words. Inconsistent names tend to fragment or bloat simple tags.

Simple tags offer no room to explain the meaning of the tag in detail, or to annotate the role of a tag (e.g. name of a television series, name of the director, describing something visually present in an image, describing the intentions of the author, describes image visual quality, describes the licensing status).

To address these issues, let’s add one level of indirection to the tagging model. First, create a file called the tag core consisting of a unique string. In theory it could be a simple string like “tree” or “Star Wars”, but because these can suffer from issues due to renaming, uniqueness, and language-neutrality, it is better to use uniformly random garbage data as the tag core. Now take the hash of the tag core and get a result like 1ca21a98

b21ccedf d10a3436 d7a1a39d 3acae032 aa688256 4c89b280 81a27cdf. Next we add tags referring to the core’s hash, such as (“tree”, “English”, 1ca2...7cdf), (“樹”, “中文”, 1ca2...7cdf). At the same time, we associate other files with the tag core hash, such as (some photo hash, 1ca2...7cdf), (some video hash, 1ca2...7cdf), (some document hash, 1ca2...7cdf). When a human performs a query, the machine will perform an extra query compared to the case of simple tags. Suppose we want to find all files associated with the/a tag named “tree”. First, we search for tags that contain the string “tree”, and make note of which tag cores these name tags point to. There might be 0, 1, 2, or more answers – but hopefully 1. Now take one of these tag cores, find every media file tag (not string tag) that points to this tag core, and take the set of file targets of these file tags as the final query result.

One extension of using tag cores is that we can create a public vocabulary of tags with universally accepted meanings. For example, there might be a publicly known tag core for the city of New York, NY, USA. When you tag your personal collection of photos, it would be beneficial to point to the publicly known tag core instead of creating your own tag core, because then you can compare your collection against other collections, or make it easier to publish in the future. And because tag cores can have arbitrary data pointing to it, it is possible to attach names in a variety of languages, links to a Wikipedia article, Earth coordinates, et cetera.

- Internal vs. external metadata

-

In any file-based system, both in traditional HFSes and in the current clean-slate proposal, metadata about a particular file can be stored within the file itself, outside the file with appropriate pointers, or both. Examples of file formats supporting internal metadata include EXIF for JPEG, ID3 for MP3, and various fields for Microsoft Office documents. The metadata is stored in some region of the file (usually the header), and the main payload is stored elsewhere within the same monolithic file. If a file containing internal metadata is transported to another location (e.g. web download), then the metadata is copied fully by default – unless extra effort is taken with a format-aware program to add/modify/remove the metadata. The problem here is that some metadata is private, in varying senses of the word.

Example: A benign case is that a thumbnail image can be embedded in a larger image file. Images can be huge (say 100 megapixels), but we like being able to quickly scroll through a collection of images while only seeing a small thumbnail (say 0.01 megapixels) of each image. But different people will have different ideas on what thumbnail size is appropriate. A power user might need 500×500 pixel thumbnails on a high-resolution screen. A smartphone user might only need a 60×60 thumbnail on a tiny screen. One user might want the thumbnail image compression to save more space at the expense of more CPU time, whereas another user might want the opposite. Some of us simply want no saved thumbnail at all, because our computers are fast and the original images are small enough to read and decode in their entirety. Distributing thumbnails with images ends up being a compromise that makes no one happy.

Example: For every song you own, you keep track of the number of times you played it, along with ratings and personal notes about what you think of the tune. If these pieces of metadata are stored within the music file, then they will likely be transmitted when you share the song with another person. But these details are personal and irrelevant to another person at best, or embarrassing and revealing at worst.

Because metadata is liable to change over time, internal metadata schemes don’t work well with systems based on immutable files. For example if you have an MP3 file with a bunch of internal tags, and you fix a typo in the song title, then you end up with a file with a different hash. If any other file contained a reference to the old MP3 file’s hash, then you would need to update those hashes to point to the new file.

Metadata is external when the main data exists in one file and the metadata exists in a different file. External metadata can exist in a couple of forms:

Some hierarchical file systems allow files to store extra content under a derived name – the feature is called alternate data streams on Windows, resource forks on Mac, and nonexistent on Unix. For example, “Dog.gif” might have a fork named “rating” where you write how many stars you rated the picture. The path to the main data is “Dog.gif”, and the path to the fork is “Dog.gif:rating”. A benefit of forks is that when you move the file, the fork automatically moves along with the file – it is impossible to have dangling or incorrect reference. In fact, a file with a bunch of forks behaves essentially like a directory with a bunch of files. A critical disadvantage of forks is that interoperability is terrible (much like hard and soft links) – forks are not supported in web protocols (you won’t download a multi-fork file without much custom hacking), the legacy FAT32 file system (used on most flash drives and camera cards), nor the Unix world in general. Making matters worse, forks are used so rarely by users that it is very easy to forget about a file having forks, or to copy a file’s main content but forget to copy its forks. Forks can be considered as dangerous and effectively dead for conveying any meaningful metadata.

Metadata can be placed in the same directory alongside the main file, such as associating “symphony.info” with “symphony.mp3”. This scheme is brittle and requires conscious user effort to rename, move, and delete both files simultaneously every time. But the advantage is that the metadata file is pretty easily seen at the same time as the main file.

Metadata can be stored in an arbitrary location, and point to the relevant file with a path name. For example a personal music database file might contain a thousand rows of entries like (title=

“Ode to Joy”, artist= “Beethoven”, storageLocation= “/home/jane/ music/ode.mp3”). This is even more brittle than storing metadata beside the main file, but a centralized database has the advantage of allowing fast and easy queries (e.g. listing all known songs alphabetically by title, filtering by artist). And finally, an external metadata file can point to the main file by hash reference. Say that a video file has the hash 4966d25c

9a3d5008 7846aa50 f7e83300 f1976a4b, and you foresee that you will never edit the video file directly (e.g. no internal metadata). Then you can create a new metadata file which says (title=“baby shower”, date=“20140628”, target=4966...6a4b) and store it somewhere. This style of operation is exactly how Git describes its data objects. But it presupposes that the file system supports hash-based queries, making this method of tagging in a traditional HFS nearly useless unless the video file is consciously renamed to 4966...6a4b. Even if it was named as such, it is brittle because if the file content is accidentally or unknowingly modified, then the hash no longer reflects the file content. But this style of hash-based external tagging is a good fit for an immutable file system because tags can be added and deleted without affecting the main file.

Although we established that external tagging has some desirable properties and might work in a hash-addressed file system, there is still one benefit of internal tagging that needs to be addressed. Sometimes we do want to transfer a file along with its tags – such as a JPEG photo with details of the camera operation (standard EXIF stuff), or an MP3 file with a good description of the song. An internally tagged file just needs one file transfer to accomplish this. External tagging forces us to transfer multiple files – however we can bundle up the main file and metadata files in a container like a TAR or ZIP file – so this is still reasonably possible.

- Tag all the things

-

So far, it was implied that tags describe readily visible aspects about a file, such as the media type, objects in a picture, title and author, etc. But an expressive metadata system allows us to represent much more types of knowledge; it is a deep rabbit hole that we will lightly dip our toes into.

For example: Normally we identify a song by its title and artist. But sometimes a song might have been performed by a number of different people over time. A piece of classical music like Für Elise will have been performed and recorded many times. While each recording is subtly or very different, they all share the same abstract melody. A more recent example is that the anime opening theme song Happy☆Material (from Mahou Sensei Negima) has been performed 8 times officially as part of the TV show. Hence there might be value in creating a tag core for each abstract melody, and associating them with concrete audio files. Once the data is entered, searching for similar songs by the criterion of abstract melody is far less error-prone than searching alternative performances by the title text. It even covers the case where a song is adapted to a different language and renamed (e.g. ひとり上手 in Japanese vs. 漫步人生路 in Cantonese).

For example: You run a photography business, where you shoot and edit photos. You want to keep the raw photo files (straight from camera) regardless of any editing work you do afterward; you save your edits as new photo files and never change or delete the originals. But you also want to remember where each edited photo came from; in particular you want the edited photo file to “point to” the original photo. Legacy HFSes make it hard to express this relationship between files, because you will probably want to store the edited photo in a completely different location (such as the customer’s folder) than the originals (such as a general archival photo stream). A partial workaround is to keep the same sequence number in both the original and the edited files (e.g. IMG_27184), but requires manual effort when saving files and retrieving files and thus is brittle. The solution is to create a tag file that points to the original and edited photo, like DerivedWork(original=(some hash), derived=(some hash)).

In this proposed system, tags are full-fledged standalone files. They can be published and discussed just like any traditional heavyweight file can. Moreover, it is permitted to create tags that refer to tags. So not only can you have a tag that says a particular photo depicts Antarctica, but you can also annotate that tag itself with information like “Bob made this note” or “I am unsure” or “This fact was added on ”.

This system also makes it possible to make private annotations about public files. Suppose you view a piece of art online, with the hash 15e8...9252. You can create an annotation file like CommentTag(target=15e8...9252, comment=“Reminds me of the street I grew up in”) and store it on your local file system. This way, you can make notes about public objects even though you don’t have permission to modify the public object directly. Also, you can upload such comments to a public repository so that many people’s feedback can be aggregated. This can be done without needing permission from the host of the original public object.

Note that I try to avoid mandatory attributes in this tag design. For example, I would not define an audio file as (title=(...), artist=(...), album=(...), rawAudioData=(...)). Because if it were defined this way, then it becomes impossible to represent facts like “this song has titles in three languages”, “there is no artist because it was published anonymously”, or “the name of the album is disputed”.

- Everything is a file

-

Every fact that can be captured about the world should be expressed as a discrete file. For example, every message in a conversation should be its own file (the overhead can be dealt with later) – not as a line of text within a monolithic mutable text file. A program’s source code could have one file per function, with the documentation comments in a separate file; these files can be woven together into a legacy-format source file to feed into existing compiler tools. If we’re talking about temperature measurements, every measured sample should be a separate file (again, instead of adding a line to a long text file). Every recorded financial transaction should be its own file.

This notion here is orthogonal to Unix’s concept of “everything is a file” – there, the idea is that every path should be readable and writable as a stream of bytes, even if the “file” is actually a mouse device or a network socket. In fact, the Unix concept doesn’t even apply to my proposal, because my notion of a file is an immutable, finite sequence of bytes – not a potentially bidirectional I/O pipe with fancy control functions.

- Data schemas

-

As soon as we moved beyond simple tags and into complex tags, we realize that not all files are created equal. For example, the first phase of the tag query looked for tags of the form (string tagName, Sha256 tagCore), whereas the second phase looked for tags of the form (Sha256 fileBeingTagged, Sha256 tagCore). It would be helpful to develop a strong typing scheme that lets us precisely target the data that we want and exclude the data that we don’t want. In particular, ad hoc file formats and heuristic/conservative scanning/matching are viewed as ugly compromises. Another reason why we might want to have schemas is to be able to find the set of all files F that contain a hash reference to some file G. To do this we need to be able to decode every file and know where its link fields are located, which implies some sort of schema.

The current situation with distinguishing file formats is bad enough already, relying on a mixture of file extensions (e.g. .zip), magic file headers (e.g. fLaC), Internet media types (a.k.a. MIME) (e.g. text/html), and other proprietary systems like Apple UTIs (e.g. org.oasis.opendocument.text). My proposed system worsens the situation by introducing many new file types, such as simple tags, tag cores, tag definitions, numeric tags (e.g. song length), and so on. The notion of a schema is mandatory in relational databases, where each row of a table must conform to some user-defined data format (e.g. int id, string name, blob data). Schemas were also tried in SGML, HTML, and XML in the form of document type definitions (DTDs), but they seem to be cumbersome, unpopular, and not rigorously checked against. Schemas are a core part of some data serialization formats like Protocol Buffers. One possible design for my proposed system is that each file starts with a 32-byte hash reference to a schema file, and then the rest of the file data conforms to the schema. A schema for all simple tag files might look like this:

schema version1 SimpleTag { // Prefixed with number of bytes, // followed by strict UTF-8 data string name; // Field is exactly 32 bytes long hash target; }However this is just a toy example. Complex schemas might allow nested structures, repetition, context-free grammars, data-dependent repetition (e.g. the number n, followed by n copies of some structure). When designing such a schema scheme, a balance needs to be struck between expressiveness, simplicity of implementation, and efficiency (no Turing machines please). Schemas for legacy file formats (say FLAC) will probably do the minimum work possible, simply declaring “this is a schema for FLAC files”, and allowing arbitrary binary data to be in the file. Certainly, it would be a bad idea to completely dissect the structure of metadata, frames, and bit fields in a file format in order to produce a fully featured schema. (In fact, FLAC is a very bad example because to detect where a frame ends, you need to parse and decode Rice-coded audio data to consume the exact correct number of bits.)

There are two major benefits if every file is prefixed with a reference to a schema. One is that it is possible to query all files of a particular type in a precise way – for example “give me all simple tags, and collect the set of all their names”. Another is that it is possible to transform between a collection of same-type files and a relational database table. For example with the simple tag schema, the corresponding database table would be CREATE TABLE SimpleTag(name TEXT NOT NULL, target BLOB NOT NULL), and each tag file corresponds to a database row. Notice that when all tag files are collected as rows in a database table, it is no longer necessary to specify the schema on each file/row individually; the table can be described once with the schema and this saves 32 bytes per tag file. Also when framing schema-based files in terms of database tables and rows, it means all the traditional techniques of database algebra, joins, and indexing can be applied toward information retrieval in my proposed system.

- Storage pools for reading

-

I hate how hierarchical file systems have an obsession about where a file is stored. For example, E:\ might be my external hard drive and /mnt/haruhi might be a remote machine connected through NFS. When I want to browse files, I am first required to navigate to the storage medium that has the file(s) I potentially want. Only then can I actually browse the user-created organization hierarchy. But what if I wanted to browse all photos among all the storage devices currently connected to my computer? Each storage device might have a “Photos” directory in its own root, but the conceptual set of all photos is spread all over places like C:\Photos, E:\Photos, /mnt/haruhi/photos, /mnt/cdrom/photos, etc.

“Ah but you can union mount everything to one common place”, one might point out. But unions mask problems when two raw directories contain items with the same name but different content (e.g. C:\Photos\0.jpg being different from D:\Photos\0.jpg, and the union can only pick one of them). Unions do not address any of the other problems with hierarchical file organization, make hard and soft links worse, and also make the semantics of mutable files/folders worse.

The proposed non-hierarchical file system fixes the file-reading problem in an elegant way. First we define the storage pool as the set of all available devices that can answer queries and read files. Next we connect devices to the pool – such as our hypothetical E drive, NFS mount, USB flash drive, and so on. Finally when we perform any kind of file query, the computer automatically asks each storage device to retrieve the requested data. For a hash query, the computer could query the fast local disks first and wait for a response before performing more costly network requests – because one answer suffices, and there is no benefit to retrieving a hash-addressed file more than once. For tag queries, the computer would always query all available devices, and probably make the results available incrementally instead of potentially waiting a long time to get complete results. In either case, the onus is on the computer software to query all the storage devices – thus freeing the user from needing to manually remember where she stored a certain file.

Conventional HFSes manage private files by the mechanism of directory and file permissions (ownership, read/write, etc.). However this leaks information because there is always some point up the hierarchy where an unauthorized user knows of the existence of private files. For example, it might be the case that the user directory /home/john is readable by everyone, and the subdirectory /home/john/private is the starting point where only John has read access. I propose to manage private files by storage attachment: if you want to see private files, you need to be able to attach a particular storage device (enforced out of band through OS-level permissions or by encryption). If you have sensitive financial documents stored on a separate device (even if it’s an HDD partition), you can unmount it when you don’t need it, so that a rogue program won’t be able to access the sensitive data.

One consequence of the storage pool concept is that it becomes practical to store a partial set of files for easy access, and attach the full collection when needed. Maybe your laptop only has a small hard drive and can only afford to store the current year’s worth of emails. At the same time, you have the rest of your email history on perhaps an external hard drive or desktop computer. Your email client software should be designed to list email messages from all available storage devices. So normally on your laptop, you only see a small set of emails for this year. But when you add a network share connection to your desktop computer, your email client can query that database as well and show you a longer list of messages. In particular, you did not need to navigate through your desktop computer’s file hierarchy to take those extra emails into account – the file system should automatically consider all the data sources that it currently has access to, when answering application-level queries such as “please list all known email messages”.

Note that the concept of a storage pool is not static; each application/process can have a different storage pool, and even individual queries or subqueries can take place over different pools. This means that for example, a password manager app can be the only one that accesses a privileged storage device containing user passwords. As another example, you might only query a single online storage device and ignore all local files if you specifically wanted to check and manipulate what exists on that online storage.

- Storage icons for status/writing

-

The concept of querying all attached storage devices works for reading files, but writing files needs more consideration. Here’s an idea: while a file is open in a viewer/editor, show an icon for each attached storage device. An icon should be green if a file is already stored on a device, gray if a file isn’t on the device but could be added, and red if a file isn’t on the device and can’t be added (e.g. read-only drive). While you are looking at a file, you can save it to one of your devices by simply clicking the appropriate storage icon. Click the C drive icon to save it onto that physical hard disk. Click the USB icon to save it to an attached flash drive. Click the cloud icon to save it to your favorite cloud storage provider.

This system actually already partially exists in the form of web browser bookmarks in Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox. Beside the address bar is a star icon that is either empty or filled. When you visit a particular web page and its URL is not in your set of bookmarks, the star icon is empty. Clicking the icon will add the current URL to your bookmarks, and the star icon becomes filled. If you navigate to a page that is already in your bookmarks, then the star icon is filled. When you click on a filled star icon, it prompts you to edit that bookmark’s metadata (page title, categorization, etc.) and also allows you to remove the bookmark (which turns the star empty).